15 years ago you might've been able to get smuggled into the U.S. for less than $1K ... now it's likely $10K+

Based on a small but growing sample size of data I've accumulated from post-arrest interviews described in court documents, here's a little insight into what migrants say they pay to cross the border

In November 2007, Border Patrol in San Diego County arrested a driver for giving a lift to two Mexican citizens who had illegally crossed the border near Tecate. It isn’t an especially unique case except for the amount that the two Mexicans said they paid to be smuggled into California, according to a federal complaint:

$500 (each, presumably).

In multiple other cases from 2007-08, migrants said they paid in the $1,000 to $2,000 range.

In August 2024, Border Patrol arrested a driver and his friend for picking up six migrants who had illegally crossed the border near Ocotillo, California. Again, not an unusual case except for the amount one of the migrants said she paid to be smuggled into California, according to a search warrant:

$20,000.

With a relatively small sample size of 46 federal human smuggling cases, I’ve extracted some data in an attempted to quantify the rising prices to cross into the U.S. illegally.

One important disclaimer: A key variable in smuggling price is where they’re coming from — i.e., it’s said to be cheaper if you’re coming from Mexico as opposed to South America. (However, all the migrants in the August 2024 case cited above said they were from Mexico, including the one who paid $20K. The others said they paid $8K, $8K, $10K and $12K. The other one is not specified.) The federal complaints I’m looking at don’t always say their home countries, but I think the data I’ve put together still captures an important overall trend.

Many of these human smuggling cases in San Diego follow a similar template:

Migrants are led by a “foot guide” to the U.S.-Mexico border, usually in the more remote desert terrain of east San Diego County, where they cross illegally.

Once in the U.S., they typically have instructions to meet a driver on or around Interstate 8.

Sometimes the migrants are apprehended before they make it to the driver if Border Patrol detects them, or sometimes the driver ends up pulled over and arrested.

Before it even gets to that point, the migrants often have to make arrangements with the organized crime groups that control the process and set the prices.

Those prices are sometimes reported by migrants to federal law enforcement officers in post-arrest interviews, and then included in the complaints.

The United Nations Office on Drug and Crime reported that in 2008 …

Migrants smuggled across the border between Mexico and the United States pay about $2,000, while migrants from beyond Mexico (and thus needing to cross multiple borders) could pay as much as $10,000.

In 2018, the New York Times reported:

A decade ago, Mexicans and Central Americans paid between $1,000 and $3,000 for clandestine passage into the United States. Now they hand over up to $9,200 for the same journey, the Department of Homeland Security reported last year. Those figures have continued to rise, according to interviews at migrant shelters in Mexico.

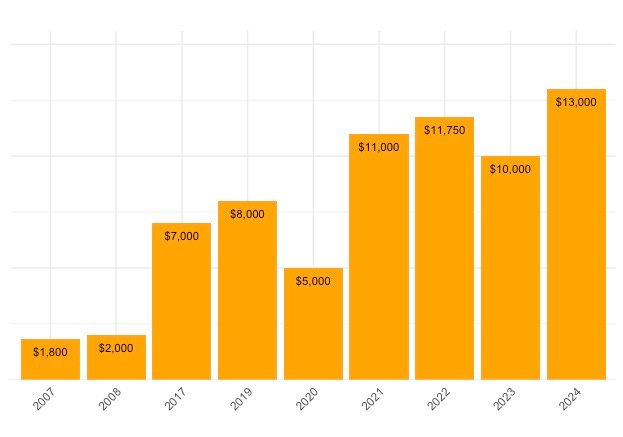

Here’s a bar graph with the yearly median amounts based on prices from my data, which are basically consistent with the above estimates (the missing years mean I don’t have data for them yet), but also shows they can get much higher:

Again, a small sample size, but it’s a 622% increase in median price when comparing 2007 to 2024.

<on a side note>

Claude helped me write the R code for the bar graph above, even though he was concerned that we were working on something “illegal and unethical.”

</side note>

The rising smuggling fees over the past few years coincides with a post-Covid surge in illegal border crossings, when there was a “pent-up demand after lockdown.” Illegal crossings have also been propelled by factors such as economic and political instability in Latin America.

More recently, a Biden executive order has led to a decrease in illegal crossings.

One last note about the data: It includes 41 cases from California, three from Arizona and two from Texas, ranging from 2007 to 2024 — and as mentioned earlier, nothing from 2009 to 2016.